Between 360 and 366 Britain appears to rebuild it’s defences and has five years of relative peace before the Scots and Picts once more band together in 366/7, this time though in a more organized and planned way that may have also involved other Germanic peoples. This event is later called the `barbarian conspiracy’.

|

| Valentinian I |

By this time Valentinian was Emperor of Rome since 364. Valentinian had received reports that a combined force of Picts, Attacotti and Scots had killed Nectaridus (comes maritimi tractus) and overcome the dux Fullofaudes in Britain. As a consequence, Britain was in a state of anarchy. Here Ammianus tells us :

“It will be sufficient here to mention that at that time the Picts, who were divided into two nations, the Dicalidones and the Vecturiones, and likewise the Attacotti, a very warlike people, and the Scots were all roving over different parts of the country and committing great ravages. While the Franks and the Saxons who are on the frontiers of the Gauls were ravaging their country wherever they could effect an entrance by sea or land, plundering and burning, and murdering all the prisoners they could take”

The Dicalidones are obviously the Caledonians. Here we also have mention of the Saxons and Franks raiding the coasts of Gaul and Britain. That these two nations appear closely allied at this time becomes apparent when we examine the early settlements in Britain that show this Frankish influence in the archaeology of Kent.

Valentinian, alarmed by these reports, set out for Britain, sending Severus (comes domesticorum) ahead of him to investigate. Severus was not able to correct the situation and returned to the continent, meeting Valentinian at Amiens. Valentinian then sent Jovinus to Britain and promoted Severus to magister peditum. Jovinus though could not remedy the situation in Britain either so Theodosius (the elder) was sent.

In 368 Theodosius arrived with the Batavi, Heruli, Jovii and Victores legions, landing at Richborough, and proceeded to London. His initial expeditions restored order to southern Britain. Later he rallied the remaining troops which had originally been stationed in Britain. It was apparent that the units had lost their cohesiveness when Nectaridius and Fullofaudes had been defeated. At this time, Theodosius sent for Civilis to be installed as the new vicarius of the diocese, and Dulcitius, an additional general. Dulcitius was Dux Britanniarum in charge of the frontier troops called Litanei so was most likely based in York. Civilis would most likely have administered from London. Ammianus tells us directly of Theodosius’ campaign in Britain :

“But Theodosius, a general of very famous reputation, departed in high spirits from Augusta, which the ancients used to call Londinium, with an army which he had collected with great energy and skill; bringing a mighty aid to the embarrassed and disturbed fortunes of the Britons. His plan was to seek everywhere favourable situations for laying ambuscades for the barbarians; and to impose no duties on his troops of the performance of which he did not himself cheerfully set the example.

And in this way, while he performed the duties of a gallant soldier, and showed at the same time the prudence of an illustrious general, he routed and vanquished the various tribes in whom their past security had engendered an insolence which led them to attack the Roman territories: and he entirely restored the cities and the fortresses which through the manifold disasters of the time had been injured or destroyed, though they had been originally founded to secure the tranquillity of the country.”

In about 369 Dulcitius had to deal with the minor stirrings of another rebellion. This one had started at the instigation of one Valentinus, a brother in law of Maximinus who would later become Praetorian Prefect of Gaul. Valentinus had been exiled to Britain because of some unknown crime he had committed in Rome. Only the power of the evil Maximinus had saved him. Ammianus again directly tells us of Valentinus :

“A certain man named Valentine, in Valeria of Pannonia, a man of a proud spirit, the brother-in-law of Maximin, that wicked and cruel deputy, who afterwards became prefect, having been banished to Britain for some grave crime, and being a restless and mischievous beast, was eager for any kind of resolution or mischief, began to plot with great insolence against Theodosius, whom he looked upon as the only person with power to resist his wicked enterprise.

But while both openly and privately taking many precautions, as his pride and covetousness increased, he began to tamper with the exiles and the soldiers, promising them rewards sufficient to tempt them as far at least as the circumstances and his enterprise would permit.

But when the time for putting his attempt into execution drew near, the duke, who had received from some trustworthy quarter information of what was going on, being always a man inclined to a bold line of conduct, and resolutely bent on chastising crimes when detected, seized Valentine with a few of his accomplices who were most deeply implicated, and handed them over to the general Dulcitius to be put to death. But at the same time conjecturing the future, through that knowledge of the soldiers in which he surpassed other men, he forbade the institution of any examination into the conspiracy generally, lest if the fear of such an investigation should affect many, fresh troubles might revive in the province.”

These words of Ammianus tell us much more about Britain than meets the eye. We see that Britain is a common place for various exiles to be sent to. Valentinus is said to `tamper’ with the exiles. A better translation would probably be conspiring with them. How many exiles were in Britain? By this account quite a few. As exiles were not exactly the most pleasant of people it is no wonder Britain was a hot bed of rebellion. That Theodosius did not investigate the conspiracy further indicates he did not want the troubles caused by Paulas Catena re-enacted. Ammianus continues relating the work of Theodosius in Britain:

“After this he turned his attention to make many necessary amendments, feeling wholly free from any danger in such attempts, since it was plain that all his enterprises were attended by a propitious fortune. So he restored cities and fortresses, as we have already mentioned, and established stations and outposts on our frontiers; and he so completely recovered the province which had yielded subjection to the enemy, that through his agency it was again brought under the authority of its legitimate ruler, and from that time forth was called Valentia, by desire of the emperor, as a memorial of his success.

The Areans, a class of men instituted in former times, and of whom we have already made some mention in recording the acts of Constans, had now gradually fallen into bad practices, for which he removed them from their stations; in fact they had been undeniably convicted of yielding to the temptation of the great rewards which were given and promised to them, so as to have continually betrayed to the barbarians what was done among us. For their business was to traverse vast districts, and report to our generals the warlike movements of the neighbouring nations.

In this manner the affairs which I have already mentioned, and others like them, having been settled, he was summoned to the court, and leaving the provinces in a state of exultation, like another Furius Camillus or Papirius Cursor, he was celebrated everywhere for his numerous and important victories. He was accompanied by a large crowd of well-wishers to the coast, and crossing over with a fair wind, arrived at the emperor's camp, where he was received with joy and high praise, and appointed to succeed Valens Jovinus, who was commander of the cavalry.”

This part of Ammianus’ writings tell us of the mysterious frontier scouts or spies called Areans or Areani. As Ammianus makes clear, these spies had been bought off by the very barbarians (Picts or Scots) who they were supposed to be reporting on. They also tell us that Theodosius had left Britain in a fit and secure state. Something must have occurred in the next few years to change all this as within 13 years another revolt had shaken Britain and Europe to its core.

In 370 Valentinian continues to clean up northern Gaul and massacres one band of Saxon raiders who had stopped their plundering and agreed to go home and lend troops to Valentinian's armies. Unfortunately Valentinian double crossed them and ambushed the Saxons, murdering every last one. It was a lesson the Saxons never forgot as the Britons would eventually find out many years later.

|

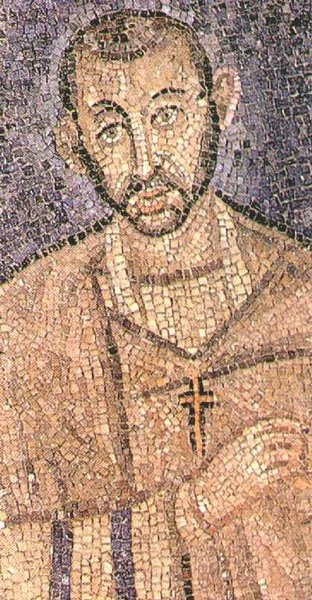

| Saint Ambrose |

These Alamannic armies would have arrived in Kent at Rutupae or Richborough as it was later known. They would then have moved onto the north to re-enforce Hadrians wall. Some may have stayed in Kent to man Saxon shore forts and some may have headed to Wales to help against the Irish Scoti. These reinforcements appear to have had the desired affect as another short period of peace comes to Britain between 370 and 383.

By 375 Gratian was now Emperor of Rome and had many troubles to contend with. The Alamanni had continued to cause problems in Gaul and in 378 a major battle ended with 30,000 Alamanni dead, if Roman records are to be believed. Gratian had caused resentment in Rome by insulting some pagan traditions. The intolerance between Christianity and paganism was starting to grow. Under Gratian and his Bishop Ambrose state subsidies that funded many pagan activities were removed. This angered many Roman senators..

|

| Gratian |

Gratian again had to fight the Alammani in 383 and it was at this time that events in Britain once again led to the fall of a Roman emperor. Is it co-incidence that at the very time Gratian is fighting Alamannic armies in Gaul, Britain, recently reinforced with Alamannic armies, suddenly breaks out in revolt? This revolt is led by one Magnus Maximus, raised by his troops as emperor of the west. He then takes the armies from Britain, heads over to Gaul and within a short time kills Gratian and enlists the help of the grateful Alamanni in his attempts to seize power over the whole Roman empire. Maximus’s Magister Equitum Andragathius was a Goth. His Praetorian Prefect was one Euodius. It is obvious from these events that the Alamannic troops posted to Britain in 374 had assumed some sort of influence, enough to raise Maximus to power to help relieve their brothers in Gaul.

Next, Maximus and the last instalment before Britain becomes independent of Roman rule and enters the early medieval period otherwise known as the Dark Ages.

Images via Wikipedia Commons.

Next, Maximus and the last instalment before Britain becomes independent of Roman rule and enters the early medieval period otherwise known as the Dark Ages.

Images via Wikipedia Commons.